Image source: Capital Regional District, BC, Canada. Image URL

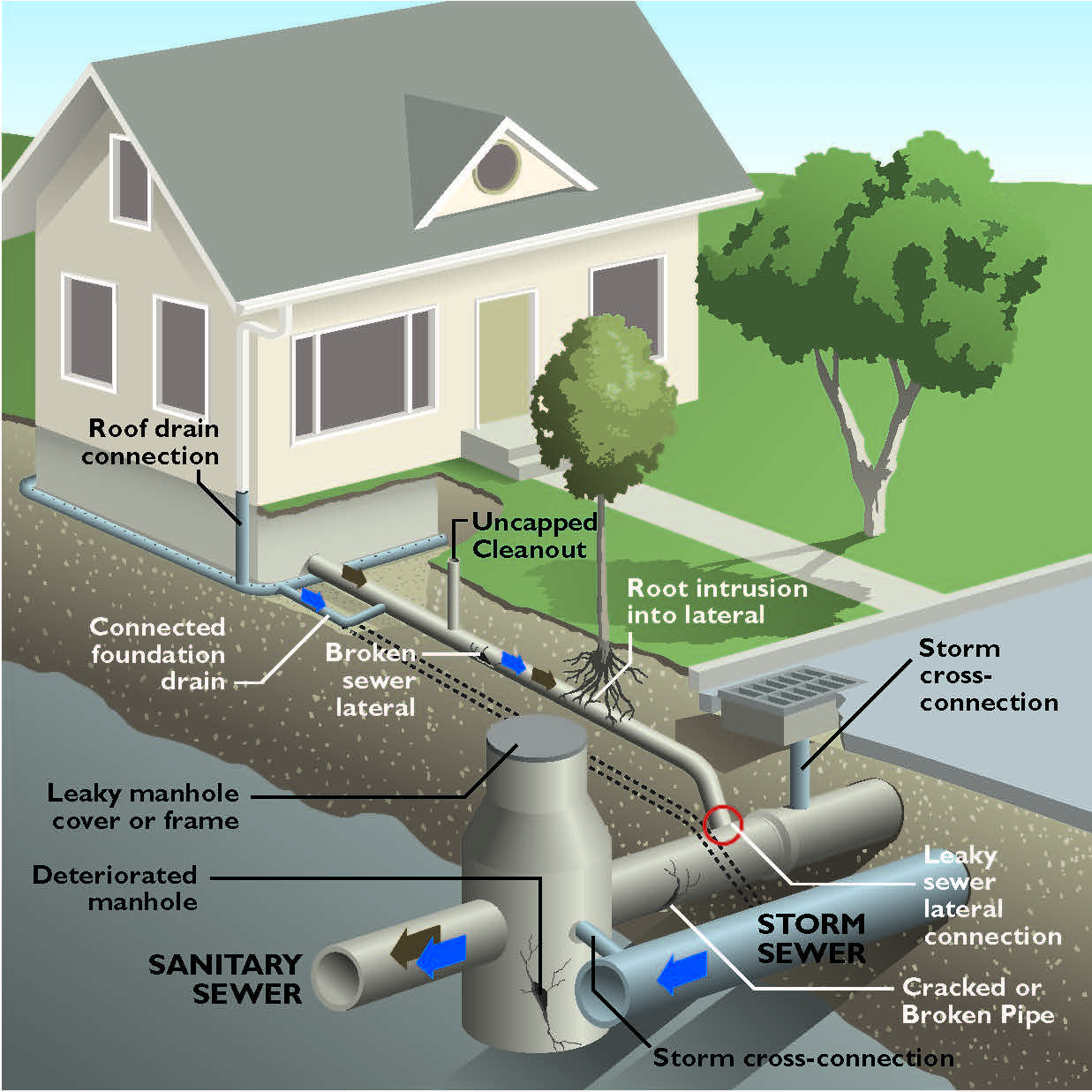

For green infrastructure enthusiasts, infiltration is a good thing – rain water soaking back into the ground where it belongs instead of flowing over dirty city streets and into local waterbodies. But for wastewater engineers, infiltration has a more sinister meaning. Inflow and Infiltration (I&I) occurs when rainwater or groundwater enters the sanitary sewer system through leaky pipes or illegal connections (downspouts or weeping tiles connected to the sanitary sewer). During dry weather, it doesn’t usually pose a problem, but during heavy rain events wastewater treatment systems can reach their capacity and bypass some or all treatment processes – or else sewage backs up into people’s basements.

Cities across Canada are taking measures to address this issue and prevent basement flooding and the release of untreated or partially treated sewage. See for example the programs of City of London, Halton Region, and City of Halifax (among many others).

Most programs follow a similar design – identify sources of inflow and infiltration, repair those on City property and provide incentives, advice, or requirements for fixing those on private property.

But there is a fundamental difference of opinion as to whether green infrastructure measures that rely on infiltration – like rain gardens, permeable pavement and bioswales – are helpful or exacerbate this problem. In particular, when property owners are directed to disconnect downspouts and weeping tiles from the sanitary sewer, should the water be redirected to permeable features or sent directly into storm sewers?

Some cities in the U.S. use green infrastructure widely, and incorporate it into I&I reduction programs. In Milwaukee, funds are available to help property owners repair sewer laterals and disconnect foundation drains, sump pumps and downspouts from sanitary sewers. The Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District also encourages water to be redirected to properly located green infrastructure instead of into storm sewers. The Blueprint Columbus program similarly addresses I&I by encouraging property owners to direct stormwater to green infrastructure on private property instead of into sanitary sewers. Many Canadian programs encourage redirecting downspouts to rain barrels or grassed areas away from building foundations.

Still, some stormwater and wastewater engineers are convinced sending stormwater back into the ground will make the problem worse. One concern is that by promoting infiltration, groundwater levels will rise and actually increase the risks for I&I. There also may be risks for other buried infrastructure, such as drinking water mains. However, the USEPA in a technical document addressing design challenges for green infrastructure in Pittsburgh, expresses no concerns about installing green infrastructure around buried utilities (except high pressure gas mains), as long as care is taken not to damage them during excavation.

More research and on the ground monitoring of the interaction between infiltration-based green infrastructure and underground pipes is needed. Taking an overly cautious approach that avoids all infiltration in dense urban areas may have negative consequences for water quality and flooding as well.

This blog was published on the Umbrella Stormwater Bulletin Issue 53.